The Life of John Travers Cornwell, VC

The King has been graciously pleased to approve the grant of Victoria Cross to Boy First Class, John Travers Cornwell, O.N. J.42563 (died 2nd June, 1916), for the conscious act of bravery below.

Mortally wounded early in action, Boy First Class, John Travers Cornwell remained standing alone at the most exposed post, quietly awaiting orders, until the end of the action, with the gun’s crew dead and wounded all round him, His age was under sixteen and a half years.

Second Supplement to the London Gazette; Friday the 15th of September, 1916.1

The life of John Cornwell was unremarkable; he played, worked and lived like so many other youths of his day. Yet he displayed remarkable courage in the course of a single day, inspiring the United Kingdom and Commonwealth in the dark days of 1916. Moreover, his memory continues to inspire countless youth throughout the Commonwealth in the hundred years succeeding his death.

Born January 8, 1900 at Clyde Cottage in Leyton, Essex (now Newham) to a working class couple Eli Cornwell, and Lily (nee King) Cornwell. Jack was proceeded by Ernest (1898) the son of Lily, and his half-siblings Alice (1890) and Arthur (1888) born to Eli’s first wife, Alice. Jack’s birth was followed by George (1901) and Lily (1905), born to Eli’s second wife, Lily Cornwell.2

Born January 8, 1900 at Clyde Cottage in Leyton, Essex (now Newham) to a working class couple Eli Cornwell, and Lily (nee King) Cornwell. Jack was proceeded by Ernest (1898) the son of Lily, and his half-siblings Alice (1890) and Arthur (1888) born to Eli’s first wife, Alice. Jack’s birth was followed by George (1901) and Lily (1905), born to Eli’s second wife, Lily Cornwell.2

Eli Cornwell was born in 1853 and served 14 years in the British Army, specifically in the 34th Regiment of Foot.3 Upon leaving the Army Eli Cornwell worked as a tram driver and milkman.4 There is scant research about the lives Lily and Alice Cornwell beyond their relationship to Jack.

During his childhood, Jack participated in the 11th East Ham Scouts Troop and was remembered as enthusiastic and committed to the program.5 In 1911 brothers Jack and George were placed in the West Ham Poor Law Union. There they would have lived in crowded living conditions with upwards of several dozens other boys and girls. Jack and George Cornwell later rejoined their family when the household moved to 10 Alverstone Road, Little Ilford. While in Little Ilford Jack attended Farmer Road School, and Walton Road School in Alverstone leaving school at the age of 14.6

After leaving school Jack sought to enlist in the Royal Navy, presumably taken by the patriotic fever sweeping many Britain’s youths. However, Jack’s parents refused to consent to his enlistment. Jack instead found employment as a delivery boy with Brooke Bond & Company and later with Witbread’s Brewery Depot.7 During this time, he continued participating with the Scouting program until the Troops disbanding due to the Troop leader’s enlistment.

Having been rejected for the Navy in 1914 on the ground of his age, he was accepted in 1915 and began his training on 27 July 1915 at HMS Vivid in Devonport.8 Jack’s training would have been strict and intense, with instruction focusing on seamanship skills, drill, and naval terminology. It is known that Jack participated in a church choir and signed a temperance pledge, agreeing to abstain from alcohol before being posted to HMS Chester.9 While in training Jack’s pay amounted to sixpence a week as a Boy Seaman Second Class. Jack was later promoted to Boy Seaman First Class on 19 February 1916 and joined HMS Chester on the 2nd of May, the day after her commissioning. Meanwhile, his father had also re-enlisted as a Private in the 26th Essex Regiment, and was later transferred to the 57th Company, Royal Defense Corps.10

After her commissioning HMS Chester was assigned to Rear Admiral Hood’s Third Battlecruiser Squadron, with the Squadron being attached to the Royal Navy’s Grand Fleet, commanded by Admiral John Jellicoe. HMS Chester'scommissioning occurred less than a month before the battle, leaving her crew no time to practice Grand Fleet gunnery or maneuvers. Simply put, her crew was completely inexperienced and unprepared for combat. Come the 15th of May HMS Chester had joined the Royal Navy’s Grand Fleet at Scapa Flow, and it is known that Jack wrote his final letter on the 23 May 1916, however, its contents are unknown.11

Since Nelson’s 1805 Victory at Trafalgar Britain enjoyed complete naval supremacy. The British public expected a victory like Trafalgar against the German High Seas Fleet. No such battle occurred. The German High Seas Fleet sank more ships than the British Grand Fleet yet failed to break British naval dominance. The German High Seas Fleet failed to secure their objective and did not attempt to attack the British in force for the remainder of the First World War.

The Battle of Jutland occurred on May 31st, 1916 with Admiral Beatty’s force sighting German ships at approximately 2:00pm. At 3:00pm Hood’s Third Battlecruiser Squadron was acting as a screening formation, cruising 25 miles ahead of the British Grand Fleet. HMS Chester was directly in between the Third Battle Cruiser Squadron and the Grand Fleets Armoured Cruiser screen, with both forces eight miles apart from HMS Chester. HMS Chester's role was to relay communications from the Third Battle Cruiser Squadron to the Grand Fleet.

Admiral Beatty’s force engaged the German fleet at 3:48pm. Because Admiral Beatty’s force had made contact with enemy the Third Battle Cruiser Squadron was sent ahead to support Beatty’s force, this is when HMS Chester likely moved to the starboard beam of Hood’s Third Battle Cruiser Squadron, placing her in a vulnerable position. At 5:30pm HMS Chester's Captain Robert Lawson moved HMS Chester to investigate the sound of presumed German gun fire, and upon advancing muzzle flashes were spotted in the distance.12 HMS Chester had unintentionally engaged the SMS Frankfurt, Wiesbaden, Pillau and Elbing of the Second German Scouting Group.13 Outmatched four to one, HMS Chester was in an extremely dangerous position.

When HMS Chester engaged the four German light cruisers to port, she was completely unable to return effective fire. This resulted from the collapse of fire control, and the crew’s ability to effectively use the ship’s ten 5.5 inch guns. Sub-Lieutenant Windham Hornby later recalled:

Occasional bangs which I heard, I attributed to our guns being fired under ‘local control’ by the battery officers or even individual Gunlayers... As a matter of routine I ‘challenged’ the after fire control position, but all I got in reply was a loud bang which may have been the bursting of the shell which exploded and wrecked the position. There was also a loud bang and shock when a shell burst against the side armour abreast of…but the burst of it drove pieces of the side armour inboard which destroyed (though at the time we did not realize it) most of the transmitting station communications (voice-pipes) with the rest of the ship.14

With HMS Chester's fire control completely disabled her guns would have fired inaccurately and without coordination. Jack’s position as the Forecastle Gun’s Sight Setter involved relaying firing solutions through voice pipes.* Sub-Lieutenant Hornby recalled that HMS Chester's voice pipes had been destroyed by German fire. The young Jack and fellow members of his gun crew had essentially been stranded at the most exposed position on the ship without directions.

The crew of HMS Chester found themselves in a treacherous position; they were outnumbered, inexperienced and unfit to engage multiple targets. Ordinary Signalman Charles Rudall later provided a simple yet fitting summary of the action, “We sighted enemy ships, four cruisers, to port and opened fire. The enemy soon got our range and were registering hits…We showed the enemy a clean pair of heels.”15 In brief, HMS Chester spotted German ships, fired, received extensive damage and retreated. She endured 17 hits in under three minutes, an average of a hit every eleven seconds. The stupendous German fire caused havoc among her crew, killing 29 crew members and injuring another 49. HMS Chester's engagement in Jutland was brief and tactically negligible, however, Cornwell’s inspiring actions proved far more important in the coming months.

Jack’s final hours were probably spent alone while the hospital staff attempted to treat the sudden influx of British casualties. Lily, Jack’s mother rushed to the hospital upon hearing of her son’s wounds, though Jack had succumbed to his wounds by the time of her arrival.16 One account states that Dr. C. S. Stephenson treated him.17 Captain Lawson noted Jack Cornwell’s bravery in a letter he wrote to Lily:

Jack’s final hours were probably spent alone while the hospital staff attempted to treat the sudden influx of British casualties. Lily, Jack’s mother rushed to the hospital upon hearing of her son’s wounds, though Jack had succumbed to his wounds by the time of her arrival.16 One account states that Dr. C. S. Stephenson treated him.17 Captain Lawson noted Jack Cornwell’s bravery in a letter he wrote to Lily:

I know you would wish to hear of the splendid fortitude and courage shown by your son during the action of May 31… ‘I cannot express to you my admiration of the son you have lost from this world. No other comfort would I attempt to give to the mother of so brave a lad, but assure her of what he was and what he did, and what an example he gave.18

Jack was buried privately in a naval coffin in Manor Park Cemetery, with a wooden peg marked 323 as his family was unable to afford a headstone.19 An uneventful life, marked by several minutes of heroism, ended tragically.

Jack’s bravery remained obscure over the next month. Conscription enforced through the “Military Service Act” came into effect on March 2nd, 1916 causing significant domestic turmoil.20 This, Dublin’s Easter Rising, and continued action on the Western Front occupied much of the publics attention. The ongoing domestic turmoil and mounting causalities on the Western Front created a need for a national hero. Admiral Beatty’s recognition of Jack Cornwell contributed to the belief that “England expects every man to do his duty.” Admiral Beatty’s Dispatches noted Jack Cornwell’s actions in his dispatches, writing:

the instance of devotion to duty by Boy (1st Class) John Travers Cornwell who was mortally wounded early in the action, but nevertheless remained standing alone at a most exposed post, quietly awaiting order till the end of the action, with the gun’s crew dead and wounded around him. He was under 16 ½ years old. I regret that he has since died, but I recommend his case for special recognition in justice to his memory and as an acknowledgement of the high example set by him.21

After the Battle of Jutland, Admiral Beatty was regarded as a public hero, however, historians have since noted his disputed failures as a tactician and commander. HMS Chester was under Admiral Jellicoe’s command giving Admiral Beatty little authority to comment on Jack Cornwell’s actions. Admiral Beatty was perhaps attempting to distract from his underwhelming performance.

With the publication of Admiral Beatty’s report Jack became a national hero, exemplifying the perceived British values of courage and devotion to King and Country. However, with this fame came public controversy. On July 8th, 1916 The Daily Sketch reported that, “England will be shocked today to learn…that the boy-hero of the naval victory has been buried in a common grave”. With the publication of this article, papers including the Daily Mirror, Daily Express and Times began to press for Jack to be reburied in a grave more fitting a spontaneous national hero. Much of the publics attention was devoted to the Admiralties overlooking a proper burial for Jack Cornwell, rather than the ongoing plight of his family. Throughout the summer the publicity became so great that Jack’s family had Ralph Whitfield, Jack’s former head teacher to act as their public representative.23

With the publication of Admiral Beatty’s report Jack became a national hero, exemplifying the perceived British values of courage and devotion to King and Country. However, with this fame came public controversy. On July 8th, 1916 The Daily Sketch reported that, “England will be shocked today to learn…that the boy-hero of the naval victory has been buried in a common grave”. With the publication of this article, papers including the Daily Mirror, Daily Express and Times began to press for Jack to be reburied in a grave more fitting a spontaneous national hero. Much of the publics attention was devoted to the Admiralties overlooking a proper burial for Jack Cornwell, rather than the ongoing plight of his family. Throughout the summer the publicity became so great that Jack’s family had Ralph Whitfield, Jack’s former head teacher to act as their public representative.23

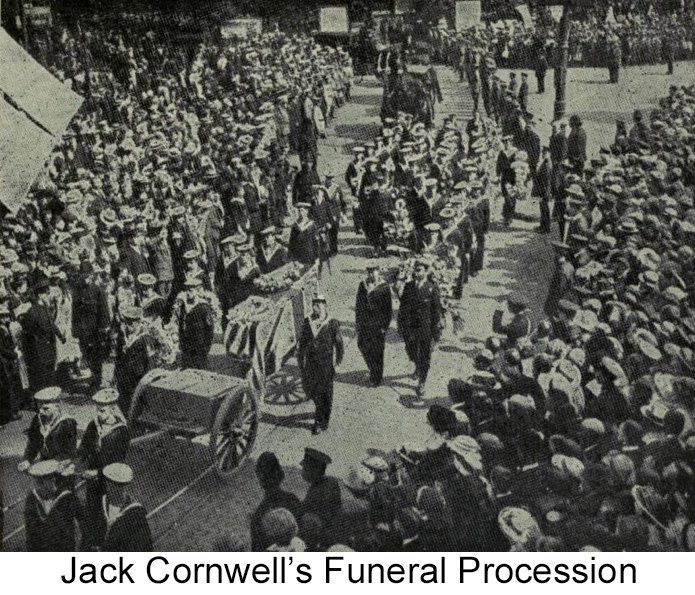

Come mid July the Admiralty had agreed to reinter Jack Cornwell in a public service at the Navy’s expense, to be held on July 29th at Manor Park Cemetery.24 The Times reported on July 31th that six Boy Seaman from HMS Chester formed an honour guard, and a wreath sent by Admiral Beatty was paraded in front of the coffin.25 Following the gun carriage were the Bishop of Barking and Councillors of East Ham, an MP representing the Admiralty and the Vice President of Navy League were also present.26

Jack’s fame extended beyond his posthumous Victoria Cross and state funeral. The Cornwell Scouting badge, “for exceptional character and duty”, and the celebration of Cornwell Day in British Schools in September 1916 are some examples of public commemoration.27 The famous picture of Jack Cornwell was commissioned, however the figure in the picture is his younger brother George.

Over the coming six weeks, Jack Cornwell’s story was moved to the sidelines, but the story again captured public attention with the announcement of his Posthumous Victoria Cross in the London Gazette on the 15th of September. His mother Lily was awarded Jack’s Victoria Cross by King George on November 16th, 1916, the youngest recipient of a Naval V.C.28 She also accepted the Bronze Cross, the highest Scouting award and witnessed Lord Baden-Powell establish the Cornwell Scouting Badge.29 This occasion was bittersweet, as Eli has died while on active duty on the 25th of October, less than a month before the presentation of Jack’s Victoria Cross.

As Jack Cornwell’s actions entered the public realm, the plight of his family was tragically forgotten. With the death of Jack and Eli Cornwell, Lily was left emotionally and financially broken. Further to her loss, Arthur (Jack’s stepbrother) died shortly before the Armistice while serving overseas in France. The Straits Times reported that Lily was employed at the British Sailors Society, however, the specifics of this employment are unknown.30 Despite the families desperate situation neither the Admiralty or Navy League would intervene. This did not stop the British government from using Jack Cornwell’s memory to fundraise over 31 000 pounds for the war effort. These funds were used for establishing six houses (cottages) for disabled veterans and an institution for “disabled sailors and soldiers”.31

As Jack Cornwell’s actions entered the public realm, the plight of his family was tragically forgotten. With the death of Jack and Eli Cornwell, Lily was left emotionally and financially broken. Further to her loss, Arthur (Jack’s stepbrother) died shortly before the Armistice while serving overseas in France. The Straits Times reported that Lily was employed at the British Sailors Society, however, the specifics of this employment are unknown.30 Despite the families desperate situation neither the Admiralty or Navy League would intervene. This did not stop the British government from using Jack Cornwell’s memory to fundraise over 31 000 pounds for the war effort. These funds were used for establishing six houses (cottages) for disabled veterans and an institution for “disabled sailors and soldiers”.31

Lily died a desolate and broken woman on October 31st, 1919, almost three years to the day she was presented with Jack’s Victoria Cross. Finally, the Navy League intervened in the family’s plight and awarded a pension of 60 pounds a year to raise the orphaned George and Lily. This sum was hardly adequate and in 1923 the daughters Lily and Alice immigrated to Canada.32

The Cornwell family donated Jack’s Victoria Cross to the Imperial War Museum in 1968. A display to commemorate Jack was unveiled with his relatives, Jutland veterans and officials in attendance. Jack Cornwell’s Victoria Cross remains at the museum today beside HMS Chester’s 5.5-inch Forecastle gun.33

The public has quietly forgotten the Battle of Jutland, now remembering it as another tremendous slaughter ranking with Verdun, The Somme, and Gallipoli. Jack too has faded from the public memory, yet small memorials to his posthumous fame remain. The British Royal Legion celebrates his actions yearly and Cornwell Mountain, British Columbia (50o 18’ 02’ N 144o 43’ 56’ W) remain testimonies to his tremendous actions.

As #49 RCSCC John Travers Cornwell V.C. enters its second century may we continue to stand our station, thereby continuing Jack’s memory and serving our community.

Any errors in preceding text are the authors own and bear no reflection to the 100th Anniversary Committee, the Cornwell Branch or Corps itself. All images were taken from the public domain.

Endnotes:

1"Second Supplement to the London Gazette." The London Gazette, 1916.

2Mary Conley, Other Combatants, Other Fronts: Competing Histories of the First World War. Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2011.

3Bill Bayliss, "Jack's Cornwell's Victoria Cross.", http://www.walthamstowmemories.net/pdfs/Bill Bayliss - Jack Cornwell-VC.pdf.

4Bill Bayliss, "Jack's Cornwell's Victoria Cross."

5Ibid.

6Ibid.

7Ibid.

8Nigel Cawthorne, Too Brace to Live, Too Young to Die: Teenage Heroes from World War 1. London: John Blake Publishing Limited, 2015.

9Mary Conley, Other Combatants, Other Fronts, 2011.

10Nigel Cawthorne, Too Brace to Live, Too Young to Die, 2015.

11"Information Sheet no 085: John Cornwell VC Chronology." The National Museum & HMS Victory. http://www.nmrn-portsmouth.org.uk/sites/default/files/John Cornwell VC Chronology.pdf.

12Nigel Steel and Peter Hart. Jutland 1916, 2003.

13Ibid.

14Ibid.

*Most accounts state that Cornwell was stationed at the Forecastle Gun, however, several accounts state that he was stationed at the First Port Gun.

15Ibid.

16Bill Bayliss, "Jack's Cornwell's Victoria Cross."

17Nigel Cawthorne, Too Brace to Live, Too Young to Die, 2015.

18Bill Bayliss, "Jack's Cornwell's Victoria Cross."

19Nigel Cawthorne, Too Brace to Live, Too Young to Die, 2015.

20Dufft, Michael. “U.K. Military Service Act.”, www.FirstWorldWar.com, http://www.firstworldwar.com/atoz/ukconscription.htm.

21Nigel Cawthorne, Too Brace to Live, Too Young to Die, 2015.

22Nigel Cawthorne, Too Brace to Live, Too Young to Die, 2015.

23Mary Conley, Other Combatants, Other Fronts, 2011.

24Ibid.

25"The Boy Cornwell." The Times, July 31, 1916.

26Ibid.

27Mary Conley, Other Combatants, Other Fronts, 2011.

28Nigel Cawthorne, Too Brace to Live, Too Young to Die, 2015.

29"Information Sheet no 085: John Cornwell VC Chronology." The National Museum & HMS Victory.

30"Sister of Jack Cornwell, V.C." The Times Straits, 1935.

31Ibid.

32Mary Conley, Other Combatants, Other Fronts, 2011.

33"Cornwell V.C. Goes to the Imperial War Museum." The Times, Nov. 28, 1968.

Bibliography:

Bayliss, Bill. "Jack's Cornwell's Victoria Cross.", http://www.walthamstowmemories.net/pdfs/Bill Bayliss - Jack Cornwell-VC.pdf.

Cawthorne, Nigel. Too Brace to Live, Too Young to Die: Teenage Heroes from World War 1. London: John Blake Publishing Limited, 2015.

Conley, Mary. Other Combatants, Other Fronts: Competing Histories of the First World War. Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2011.

"Cornwell V.C. Goes to the Imperial War Museum." The Times, Nov. 28, 1968.

Dufft, Michael. “U.K. Military Service Act.”, www.FirstWorldWar.com, http://www.firstworldwar.com/atoz/ukconscription.htm.

"Information Sheet no 085: John Cornwell VC Chronology." The National Museum & HMS Victory. http://www.nmrn-portsmouth.org.uk/sites/default/files/John Cornwell VC Chronology.pdf.

"Second Supplement to the London Gazette." The London Gazette, 1916.

"Sister of Jack Cornwell, V.C." The Times Straits, 1935.

Steel, Nigel and Peter Hart. Jutland 1916: Death in the Grey Wastes. London: Orion Books, 2003.

"The Boy Cornwell." The Times, July 31, 1916.

Additional Articles:

History of John Travers Cornwell, VC by Phillip Bingham